We’ve passed into the wee hours and out of Columbus Day, and I’m still browsing commentary on the holiday. It’s an awkward feeling. After all, it’s a bit hard to figure out what to do with a holiday that holds within it a celebration of all the following: the greatest single-shot cultural and biological exchange in human history; the destruction and domination of myriad indigenous cultures via military conquest and disease; and also, implicitly, the of everything that followed Columbus’ arrival in this hemisphere, from the thirty-five states that now exist on this soil, to the existence of almost everyone I know.

It’s awful, after all, to celebrate an event that led to massive genocide; but it’s hard as well to follow certain disavowals to their logical conclusion, and wish away oneself and the world that exists now. And it is, of course, complicated by the fact that for me, as for many commentators, any discussion of the meaning of Columbus Day veers swiftly into confrontation with “the Other.” Some traces of Cherokee blood notwithstanding, I am positioned from the outset at the vantage point of the conquering white male, ineluctably privileged and unable to assume, directly, the Native American viewpoint.

I’ve read several approaches to this conundrum. There is condemnation of the holiday itself and Columbus as individual, which is fine as it goes – the holiday, as we’ve already established, makes us feel weird, and Columbus personally did lots of horrible things. There is also (of course) plenty of silly, slightly gross, rather self-indulgent whinging by rightists who feel slighted that anyone else should feel ambivalent about the holiday. I’ve read columns and comics that attempt to re-appropriate the holiday – Indigenous People’s Day, Bartolomé Day – and essays proposing to split the difference and ignore the entire thing in favor of Canadian Thanksgiving.

And yet the effort to square the circle is a difficult thing to abandon, and it strikes me that to only decry Columbus Day as a day of horror and a celebration of a genocidaire risks the relinquishment of a true stake in this land, and overlooks other key themes in the history of the Americas: encounter, hybridity, agency. As soon as Cristoforo Colombo’s ships hove in view of Guanahani/San Salvador, encounter became inevitable, and hybridization followed. And this encounter took a multitude of forms, molded by the actions of Native Americans who were anything but helpless victims, and produced a hybrid hemisphere which is with us yet.

Indigenous agency and hybrid polities

Encounters of violence, we know, were inextricable from the process, and the first Europeans to arrive in (particularly Spanish) America were master practitioners of violence: death by fire and the sword ensued, and rape, and enslavement. And yet these encounters of violence swiftly shifted, almost from the beginning. What emerged was neither straightforward victimization of indigenous peoples by European invaders, nor heroic resistance, but a many-sided struggle over who would shape and benefit from the terms of encounter. Matthew Restall’s Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest serves as an exemplary literature review of scholarship that reveals Native Americans not as merely victims, but as agents. Local leaders collaborated with or resisted Spanish conquest strategically, to maximize their own local position, often at the expense of other indigenous leaders. Seen in this light, Spanish conquistadores were not an irresistible new force to arrive on the scene, but a (very powerful) new player in local political games.

Just as the political and military history of conquest in the Americas is variegated, the fabric of the polities that emerged, and that are in a continued process of formation today, are complexly woven from indigenous and grafted influences – particularly in Latin America, where large indigenous populations have survived in Mesoamerica and the Andes. For centuries, indigenous people have navigated incorporation into the Spanish empire and into independent republics, responding to changing circumstances by adapting political strategies for preserving spheres of local power and autonomy. Again, these histories have seen plenty of exploitation, but local collaboration often led to exploitation by indigenous local notables, such as the kurakas of the Quechua-speaking Andes, just as by European colonists and “mistis.” This is a perverse sort of agency, but it does denote agency, as opposed to mere annihilation – what Restall calls the “Myth of Native Desolation.”

Today, attempts to draw upon a rhetoric of pure “resistance” often mark gambits by individual leaders to stake out an ideological territory and advance their own personal leadership, as in the internecine struggles over leadership of the indigenist Left in Bolivia, where relative radicals of that movement have lost out to relative moderates like Evo Morales, whose core constituency – the cocaleros – represents a particularly postmodern sort of indigenous identity, well-adapted to transnational capitalism at the same time that it embraces “ancient” symbols. Encounter seen through this lens is a profoundly political phenomenon, producing hybrid polities. It is, as much as anything, this hybridity that is worthy of celebration on this day of doleful remembrance, as a celebration of the condition of the Americas as a whole, and of the perpetual encounter which has produced the hybrid cultures of our hemisphere.

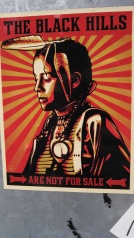

Does Columbus himself deserve a holiday? Surely not. But we need, perhaps now more than ever, a holiday which forces us to remember and reflect upon the complexities and ambiguities of our hemispheric past; a holiday on which we celebrate not just resistance, but resilience; and which spurs us on to the work of building a more just Americas. The reality is that many descendants of native peoples still suffer deeply in this hemisphere, from Patagonia to the Arctic Circle. Throughout the hemisphere action is desperately needed to put an end to outright discrimination and systemic blights (the dire state of the reservation system in the US springs to mind, as does the battle to bring justice to victims of a much more recent genocide in Guatemala). Other struggles are even more lateral, structured around the environment, sustainable development, and education issues. If Columbus Day reminds us of nothing else, it should remind us of the tremendous amount of work that remains to be done in building a more just Americas. That is a cause for pain, and a cause worth celebrating.

All our ancestors within us

I read today a long piece – worth reading – on the descendants of Columbus’ first interlocutors in the New World, the Taino of Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and the Bahamas. Long thought to have been wiped out, the author finds them to be very much alive, and in the midst of a resurgence of identity, mannered and intentional as these things always are:

In Puerto Rico’s central mountains, I came upon a woman who called herself Kukuya, Taíno for firefly, who was getting ready for a gathering of Indians in Jayuya, a town associated with both revolution and indigenous festivals. She had grown up in New York City but had lived in Puerto Rico for 35 years, having been guided to this remote community, she said, by a vision. Green-eyed and rosy-cheeked, she said her forebears were Spanish, African, Mexican and Maya as well as Taíno.

“My great-grandmother was pure-blooded Taíno, my mother of mixed blood,” she said. “When I told people I was Taíno, they said, ‘What, are you crazy? There aren’t any left!’ But I don’t believe you have to look a certain way. I have all of my ancestors within me.”

As citizens of the Americas (and almost regardless of our physical bloodlines, though these, too, are often as tangled as Kukuya’s, admitted or no) we carry within our political selves all our ancestors, Bartolome de las Casas and Christopher Columbus, Sheridan and Sitting Bull, resistance fighters, collaborators, and conquerors. Columbus Day – this uncomfortable holiday, a memorial to a genocide and to tremendous achievements of hybrid cultures, should remind us of the imperative to encounter others upon an equal ground, and to continue to work to better this patch of earth on which we find our hybrid selves.